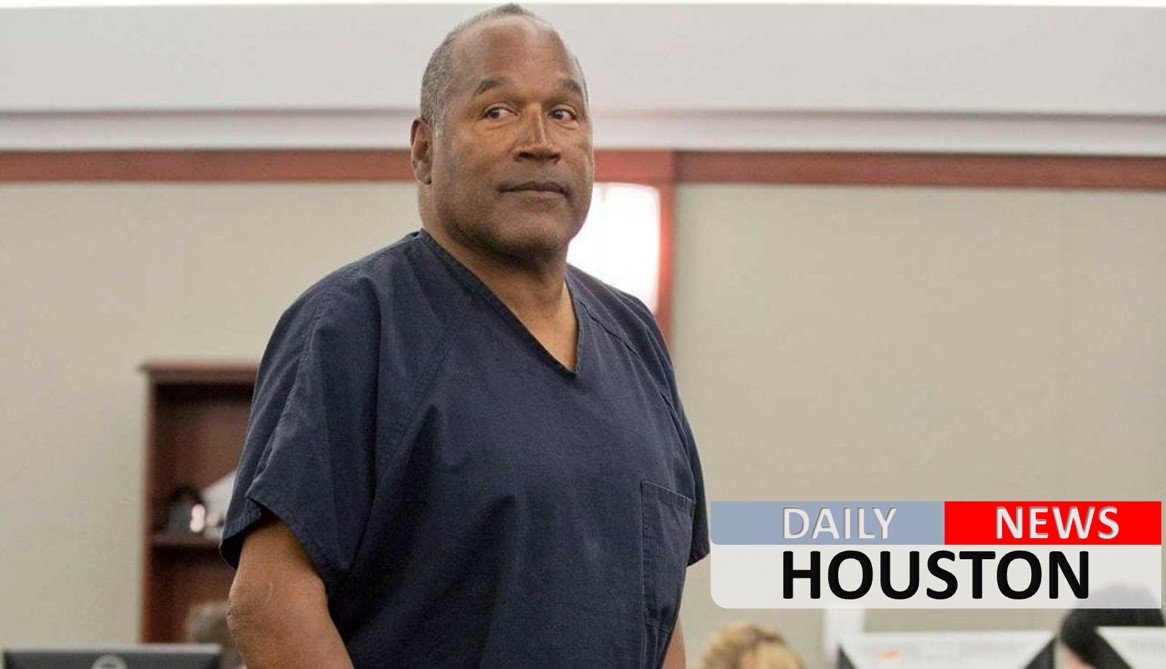

O.J. Simpson, the former football star, TV pitchman and now Nevada prison inmate No. 1027820, will have a lot going for him when he asks state parole board members this week to release him after serving more than eight years for an ill-fated bid to retrieve sports memorabilia.

Now 70, Simpson will have history in his favor and a clean record behind bars as he approaches the nine-year minimum of his 33-year sentence for armed robbery and assault with a weapon. Plus, the parole board sided with him once before.

No one at his Thursday hearing is expected to oppose releasing him in October — not his victim, not even the former prosecutor who persuaded a jury in Las Vegas to convict Simpson in 2008.

“Assuming that he’s behaved himself in prison, I don’t think it will be out of line for him to get parole,” said David Roger, the retired Clark County district attorney.

Four other men who went with Simpson to a hotel room to retrieve from two memorabilia dealers sports collectibles and personal items that the former football star said belonged to him took plea deals in the heist and received probation.

Two of those men testified that they carried guns. Another who stood trial with Simpson was convicted and served 27 months before the Nevada Supreme Court ruled that Simpson’s fame tainted the jury. Simpson’s conviction was upheld.

Prison life was a stunning fall for a charismatic celebrity whose storybook career as an electrifying running back dubbed “The Juice” won him the Heisman Trophy as the best college player in 1968 and a place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985.

He became a sports commentator, Hollywood movie actor, car rental company spokesman and one of the world’s most famous people even before his Los Angeles “trial of the century,” when he was acquitted in the killings of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman.

Simpson, appeared grayer and heavier than most remembered him when he was last seen, four years ago.

He will appear Thursday by videoconference from the Lovelock Correctional Center, to be quizzed by four state parole commissioners in Carson City, a two-hour drive away.

Two other members of the board will monitor the hearing, said David Smith, a parole hearing examiner.

The commissioners will have a parole hearing report that has not been made public, plus guidelines and worksheets that would appear to favor Simpson. It plans to make its written risk assessment public after a decision.

They will consider his age, whether his conviction was for a violent crime (it was), his prior criminal history (he had none) and his plans after release, Smith said.

Nevada has about 13,500 prison inmates, and the governor-appointed Board of Parole Commissioners has averaged about 8,300 annual hearings for the past four years. The rate of inmates who are granted parole in discretionary hearings held as they approach their minimum sentence, like Simpson’s, averages about 82 percent.

The same four board members also have experience with Simpson, having granted him parole in July 2013 on some charges — kidnapping, robbery and burglary — stemming from the 2007 armed confrontation. The board’s decision left Simpson with four years to serve before reaching his minimum time behind bars.

Board members Connie Bisbee, Tony Corda, Adam Endel and Susan Jackson noted at the time that Simpson had a “positive institutional record,” with no disciplinary actions behind bars.

Simpson’s lawyer, friends and prison officials say that hasn’t changed.

“He’s really been a positive force in there. He’s done a lot of good for a lot of people,” said Tom Scotto, a friend from Florida whose wedding Simpson was in Las Vegas to attend the weekend of the robbery.

Scotto said he visits or talks with Simpson every few months.

Simpson leads a Baptist prayer group, mentors inmates, works in the gym, coaches sports teams and serves as commissioner of the prison yard softball league, Scotto said.

Scotto will be among the 15 people with Simpson in a small conference room at the prison, along with Simpson’s lawyer, Malcolm LaVergne, daughter Arnelle Simpson and sister Shirley Baker.

A parole case worker, two prison guards and a small pool of media also were expected, along with Andy Caldwell, a retired Las Vegas police detective who investigated the Simpson case, and Bruce Fromong, one of the memorabilia dealers who was robbed.

“I don’t want to offer an opinion,” said Caldwell, now a Christian minister in Lyons, Oregon. “I’m just curious to see how everything unfolds.”

Fromong said he will attend as a victim of the crime but will be “trying to be good for O.J.” He said he suffered four heart attacks and severe financial losses as a result of the robbery but later forgave Simpson.

The other collectibles broker, Alfred Beardsley, died in 2015.

In a nod to Simpson’s celebrity, officials will let the proceedings be streamed live, and the board plans a same-day ruling. A decision usually takes several days.

Laurie Levenson, a Loyola Law School professor and longtime Simpson case analyst, predicted a “tsunami” of public attention if Simpson wins release.

“If this is the ordinary case, he will be paroled,” Levenson said. “But O.J. is never the ordinary case.”

Al Lasso, a Las Vegas defense attorney who has followed the case but does not represent Simpson, said any other defendant in a similar case probably would have gotten probation, not prison.

“I think he spent more than enough time in prison for a robbery in which he didn’t even have a gun himself,” Lasso said.

But Michael Shapiro, a New York defense lawyer who provided commentary during Simpson’s conviction in Las Vegas in 2008 and his acquittal in Los Angeles in 1995, said freedom was no certainty.

“The judge believed he got away with murder,” Shapiro said. “That’s the elephant in the room. If the parole authorities feel the same way, he could be in trouble.”