The new $249 gadget, released in February, automates much of the job of a certain kind of photographer. You place the 2-inch high white square on a surface, preferably someplace frequented by children or pets. It automatically captures any “candid” scenes it determines are worthwhile with its wide-angle lens.

I spent a week with the camera, planting it on countertops, floors and shelves. Unfortunately my cat and bunny both passed away last year, so Clips only had children to work with. Luckily, my children are extremely good looking.

Even so, the resulting photos and videos had a common, soulless look to them. The wide-angle meant they were busy, with too much in focus and no appealing composition.

Essentially, Clips combines the hands-off approach of a surveillance camera with the visual style of a surveillance camera.

And yet, for a camera that silently watches you, Clips doesn’t feel creepy. Google (GOOG) has been careful to avoid raising any privacy red flags. It stores all images and videos on the device. You preview photos using the Clips Android or iOS app over a one-to-one WiFI connection, and manually choose which ones to save to your smartphone.

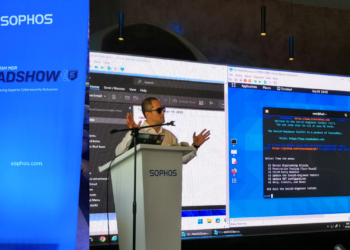

An unedited Google Clips photo of aforementioned cute children.

While it might not succeed as a camera, it does raise interesting questions about what makes a photograph “good,” and if you can ever program an algorithm to make art.

“The act of photography is the act of expression,” said photographer Ben Long, author of “The Complete Digital Photography.” “The [Clips] algorithm would just be the expression of the photographic ideas of whoever wrote that algorithm, minus the knowledge of what makes the scene around them interesting.”

To come up with its special sauce, the Clips team asked professional photographers working at the company what they believe makes a good photo.

The software looks for children, animals, and faces, preferably within three-to-eight feet of the lens. Clips likes movement, but tries to avoid blurry photos and can tell when something is blocking the lens, like the hand of a curious child. It learns the faces of the people you save the most and takes more pictures of them. It is programmed to have a preference for happy, smiling faces.

Even when Clips follows the rules, the resulting photographs are mostly un-Instagrammable. Current trends favor highly stylized, painstakingly staged shots for social media. While cameras have gotten better at capturing reality, people have grown sophisticated enough to appreciate more abstraction in photography.

But the problem with Clips isn’t just the execution or quality of photos. It’s the underlying assumption that you can program a device to replicate the decisions that go into making a good picture.

“You can try to come up with all the rules you want for photography, and you can try to follow them perfectly and still come up with some very crappy photos,” said Long after reviewing my test shots.

Rules can’t predict the many small decisions a photographer makes in the moment, like where to stand, what moment to press the shutter button, or what part of an image to expose or keep in shadows. The mere presence of a photographer also has an influence on the picture. Taking pictures is an inherently social experience, says Long. The subject is always reacting to the photographer in some way.

Clips might not take off, but it is a sign of what could be next for photography. Companies are forging ahead with technologies that will automate and change the field. They’re driven in part by the desire to improve smartphone photography without having to make giant phones. For example, cameras like the newer Pixel and iPhones use software to convincingly fake a shallow depth-of-field effects. The Light L16 camera uses 16 separate cameras to create one detailed image file that can be edited after the fact.

Clips builds on years of Google’s own work by automating parts of photography. Google Photos has an “Assistant” option that handles some of the duller parts of managing a massive amount of photos, like choosing and editing the best shots, and making movies from videos.

Google doesn’t see Clips as a replacement for photographers, but as another tool they can use.

“We see the importance of a human being in this,” said Google’s Juston Payne, the Clips product lead. “It can’t move itself or compose a shot or get a good angle. The person is still exerting creative control, AI is just pressing the shutter button … We think of it as a collaboration between people and AI and they are both completely necessary.”